JavaScript is a bit different from the strict and rigid reality of C/C++ and Object Pascal that many developers are used to, and this is especially visible when it comes to event handling.

In this article I will focus on a relatively advanced topic, meant for those of you that implement components and widgets yourself. Especially if you are writing components that is meant to be used by JavaScript developers outside your object pascal ecosystem – or sold as a commercial package for Quartex Pascal.

Custom events?

As you no doubt have noticed QTX supports both event paradigms:

- Modern delegate objects (also called multi-cast events)

- Classical procedural events

I have touched on delegates before so I wont rehash too much. But in short: delegates as events as object. Objects that you can attach any number of procedural handlers to, and they all fire in the same sequence you added them. So yes, you can have 100 separate OnClick handlers attached to a button if you like.

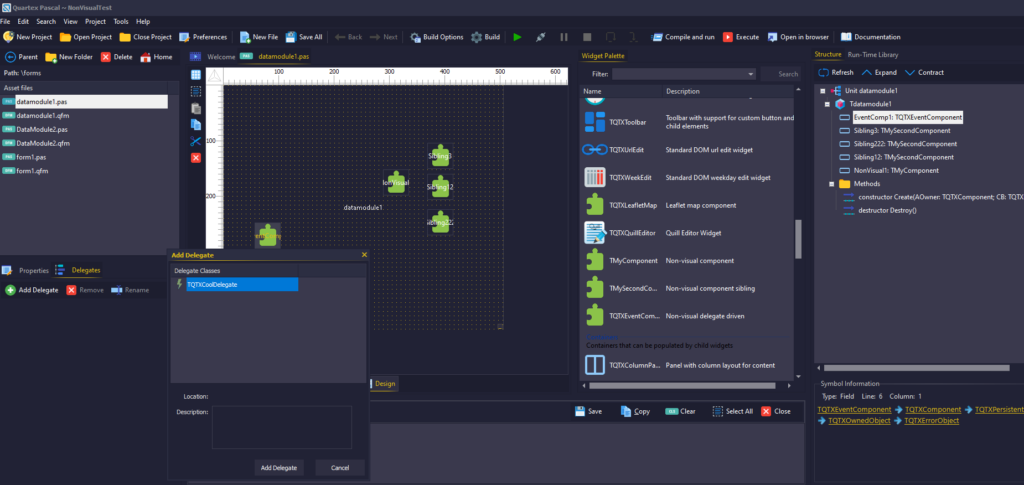

So in this article we will cover the full path from creating the event your component issues – to making delegate object that you register with the IDE. Once registered the delegate becomes available in the ‘add new delegate’ dialog for your components.

Widget vs Component?

Before we continue we need to talk about the differences between the DOM (browser) and NodeJs (server coding). All visual controls in QTX inherits from TQTXWidget. This is a root class that creates a specific DOM element, manages it during it’s lifecycle -and finally destroys the element in the destructor.

More or less all visual DOM elements expose the same delegates (or supports the same events). Delegates such as Mouse, Pointer and Keyboard are all intrinsic. Meaning, that we did not manually implement the mechanisms behind it – we simply wrapped what was already there in the browser.

With non-visual components that inherit from TQTXComponent the story is very different. The DOM is all about visual elements that has a handle (a reference to the HTML element itself) that we manage. So when a TQTXWidget is created, it also creates the HTML element that it represent -and thus absorb all the features DOM elements have. Delegates included.

With TQTXComponent that doesn’t happen, because by default there is no underlying element to manage. There is no handle property that we can typecast and get easy access to event mechanisms that are already there. The positive side of this is that it grants us complete freedom.

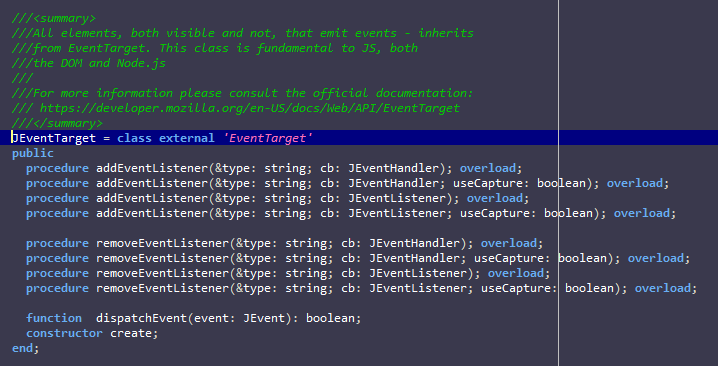

The EventTarget class

Hidden in the qtx.delegates.pas unit there is a class definition called JEventTarget. This is (simply put) the class you need to deal with event subscription and dispatching the JavaScript way.

Thankfully, the class is small and fairly self explanatory:

If you are wondering why on earth they named this event-target when it’s more of an event-source, you are not alone! The rationale behind the name is that it must be seen from the event object’s point of view; where the event goes into this target and is dispatched to the subscribers.

Note: If you are snooping around the unit you will also notice another class, JEventEmitter, that looks more impressive. But that is a NodeJS exclusive class. If you want to write code that works for both the DOM and NodeJS then stick to JEventTarget.

Since our TQTXComponent has the scaffolding in place to manage a ‘handle’ but doesn’t magically create anything by default, the handle property is actually the perfect spot to store our JEventEmitter object!

Alright, enough theory – let’s setup the basics:

type

// Forward declaration

TQTXEventComponent = class;

// Our constructor callback

TQTXEventComponentConstructor = procedure (AComponent: TQTXEventComponent);

// Our class definition

TQTXEventComponent = class( TQTXComponent )

protected

function GetEventTarget: JEventTarget; virtual;

property EventTarget: JEventTarget read GetEventTarget;

public

constructor Create(AOwner: TQTXComponent; CB: TQTXEventComponentConstructor); reintroduce; virtual;

destructor Destroy; override;

end;

constructor TQTXEventComponent.Create(AOwner: TQTXComponent; CB: TQTXEventComponentConstructor);

begin

inherited Create(AOwner, procedure (AComponent: TQTXComponent)

begin

SetHandle( new JEventTarget );

if assigned( CB ) then

CB( self );

end);

end;

destructor TQTXEventComponent.Destroy;

begin

SetHandle( unassigned );

inherited;

end;

function TQTXEventComponent.GetEventTarget: JEventTarget;

begin

result := JEventTarget( GetHandle() );

end;

Since the public Handle property just exposes a plain-old untyped THandle, I have made a protected, typed property called EventHandle that casts the Handle for us. If you want to make that property public is up to you. I added it to make access easier from within the component.

Triggering events

Now that we have a base-line component for dealing with event subscription, removal and dispatching – how exactly do we trigger an event?

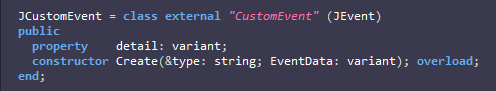

Before we can dispatch an event we first need to understand what JavaScript expects from us. And what it wants is that we isolate the data for the event in a separate object. So we end up with two parts here: first the event itself, and secondly the data structure we want to inform our subscribers about.

Let’s look at the actual event itself. JavaScript provides a special class for this called ‘CustomEvent’. This inherits from JEvent so it has all the bells and whistles we need. As you can guess from this class definition, the detail field is where it wants to store our data.

Since we will be needing a type for our detail field -let’s define a JS friendly class for that first. Classes that will be used directly with JavaScript should inherit from JObject rather than TObject. Let’s setup two fields for our event:

JMyData = class( JObject )

mdValue: int32;

mdText: string;

end;

With that in place, let’s copy the JCustomEvent definition in full and change that variant datatype to our new JMyData type. There is no point inheriting out from JCustomEvent since we want to alter that detail datatype:

JMyCustomEvent = class external "CustomEvent" (JEvent)

public

property detail: JMyData;

constructor Create(&type: string; EventData: variant); overload;

end;

With both the data and event itself defined, let’s make life easier for ourselves. Instead of having to create the event object all over the place – let’s isolate it in a method we can use:

procedure TQTXEventComponent.SignalCool(const Value: int32; const Text: string);

begin

var lEvent := JMyCustomEvent.Create('cool',

class

mdValue := value;

mdText := text;

end);

EventTarget.dispatchEvent( lEvent );

end;

If you are looking at that code scratching your head about the ‘class’ keyword in the middle of a constructor – that is understandable. This is a unique and awesome feature called an inline class. This feature makes JavaScript coding more sane, especially when wrapping external libraries.

Inline class

When you define a normal class in Quartex Pascal that inherit from TObject, you actually get a full VMT (virtual method table) powered object! We are not simply emitting paper thin JavaScript object. The compiler operates more or less exactly like Delphi or Lazarus does and emits a VMT structure for each instance. Without this it would be impossible to support virtual and abstract methods, inheritance, partial classes and interfaces.

But the VMT doesn’t play well with JavaScript, because JavaScript expects a clean structure. We have a couple of options at hand for this scenario:

- Inherit from JObject instead of TObject

- Use a record type

- Create an empty JS object and manually add name/value pairs

- Use an inline class

The reason I used the inline class approach is simply that it’s easier. You don’t need to pre-define a type, you don’t need to create an instance of said definition, and you can sculpt the object ad-hoc there and then. It also protects the field and method names so these are not scrambled if you compile with obfuscation (records are not protected and should only be used internally by your code, not as parameters for a JavaScript call).

So this code:

type

TMyData = class( JObject )

mdValue: int32;

mdText: string;

end;

var data := new TMyData;

data.mdValue := 12;

data.mdText := "hello there";

Can be more elegantly written as:

var data = class

mdValue := 12;

mdText := "hello there";

end;

Since there is no need for us to keep the data once it’s dispatched, I simply defined it in-place as a parameter. You can use a variable for it if you like, but there really is no need and just wastes memory.

Making a delegate object

If all you want to do is add handlers at runtime via code and trigger events manually – you are all set. Simply expose the EventTarget property as public, and you can add as many handlers as you like.

But since the whole point of a rapid application development (RAD) tool is to quickly build up functionality through drag & drop – we really need to create a proper delegate class that can be registered with the IDE.

First we are going to need a procedural event type which represents the handler that the IDE will automatically create for you when you add a delegate:

type

TQTXCoolHandler = procedure (Sender: TQTXCoolDelegate; EventObj: JMyCustomEvent);

Next we need the actual delegate class, this is the class that is registered with the IDE later. I know this looks like a lot of work, but it’s pretty much copy & paste from the RTL and just change the datatypes to match:

TQTXCoolDelegate = class( TQTXDelegate )

protected

procedure DoExecute(Event: JEvent); override;

function GetEventName: string; virtual;

public

procedure Bind; reintroduce; overload; virtual;

procedure Bind(Handler: TQTXCoolHandler); reintroduce; overload; virtual;

published

property OnExecute: TQTXCoolHandler;

end;

function TQTXCoolDelegate.GetEventName: string;

begin

result := 'cool';

end;

procedure TQTXCoolDelegate.DoExecute(Event: JEvent);

begin

if assigned(OnExecute) then

OnExecute(self, JMyCustomEvent(Event) );

end;

procedure TQTXCoolDelegate.Bind;

begin

inherited Bind( GetEventName() );

end;

procedure TQTXCoolDelegate.Bind(Handler: TQTXCoolHandler);

begin

var lTemp: TQTXDelegateHandler;

asm

@lTemp = @Handler;

end;

inherited Bind( GetEventName(), @lTemp);

end;

And the final piece is that we register our fancy new delegate with the IDE. This is done through attributes on the component(s) that support said delegate. So if you have an event called “cool” in other components, you can register the delegate for that class as well.

So let’s attach the delegate to the component we created earlier:

[BindDelegates([TQTXCoolDelegate])];

TQTXEventComponent = class( TQTXComponent )

protected

function GetEventTarget: JEventTarget; virtual;

property EventTarget: JEventTarget read GetEventTarget;

public

procedure SignalCool(const value: int32; const text: string);

constructor Create(AOwner: TQTXComponent; CB: TQTXEventComponentConstructor); reintroduce; virtual;

destructor Destroy; override;

end;

And that is it! You now have a non-visual component that supports established JavaScript event management, and a delegate class that registers with the IDE and that shows up in the “new delegate” dialog!

Tips and suggestions

If every event your component supports have different data then there will be a bit of copy and pasting for each event. I strongly suggest you plan your events before you begin writing delegate classes.

Also remember that you can use partial classes to put the delegates in their own unit, just to make large and complex components with many delegates more manageable.

I also suggest that you support the old procedural events at the same time. I usually define these first while I work, because it’s so easy to change them when needed. Once my code is fully operational and the events deliver what I need them to do – then I write delegates that match.

If the data you deliver in your delegates is the same for several events, then you can just use inheritance to cut down on the work. Simply override the GetEventName() and you can re-use the baseline.