In the Quartex Pascal RTL we support both traditional pascal events, like people are used to from Delphi or Freepascal, as well as delegate objects native to JavaScript. Most widgets exposes standard events like OnClick when it’s useful, and if you need more specific event handling you can attach a delegate for it.

Delegates?

A delegate is an object that represents your event-handler, the procedure that should be executed when the event fires. The benefit of a delegate is that it allows you to attach as many handlers as you like to any given event. Internally in the JavaScript runtime when an event is triggered, it will traverse the delegate array associated with the event – and call each handler in sequence.

So you can attach 100 OnClick handlers to a button if you like, and they will all fire in the same sequence as you added them. This is very useful since you can attach to widgets from the outside rather than override methods or mess with the internal logic.

You can read more about event delegation in JavaScript here.

Delegate handlers

Delegate handlers are somewhat different in Quartex Pascal than you expect. We don’t shield you from the JS elements we have wrapped. Instead we have provided utilities that simplify working with these raw JS style handlers.

Let’s look at a pointer event (similar to mouse but works well on touch devices):

procedure HandleClick(Sender: TQTXDOMPointerDelegate; EventObj: JPointerEvent);

The important part in the above handler is the EventObj, which is the actual PointerEvent object from Javascript. We have painstakingly created a wrapper class for it (which is why it comes in as JPointerEvent) that allows you to work with the raw JavaScript object directly.

The most important property of any native JavaScript event object, is no doubt the target (and currentTarget) property. This contain the handle of the element you have clicked or interacted with.

Finding the instance

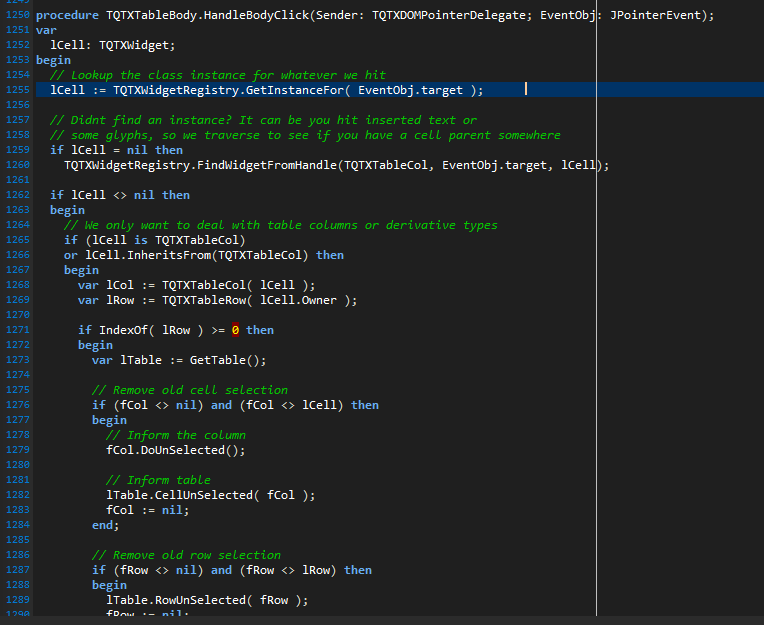

If you have created your own widget that maintains several child elements, you have two choices: either you attach a delegate to each child, which results in hundreds or potentially thousands of delegate objects being created. Or, usually more prudent, you attach a single handler to the widget itself (the container of the children) and then work out what child the user has interacted with.

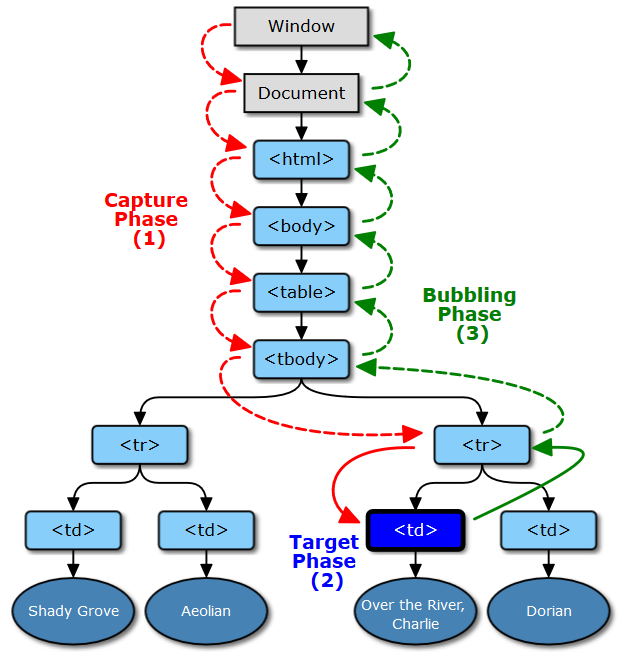

This works because JavaScript events bubbles upwards. So whenever you click anything, the event will first fire on the document, then trigger in the application display element, then the form, then panels or anything else beneath the mouse pointer (and so on). Think of it like a deck of cards where the event will fire starting from the card at the bottom – and bubble upwards toward the top. The current card is represented by the currentTarget property, while whatever you hit on that card (child) is referenced in the target property.

To find the widget instance (class instance) that a handle belongs to, we can use the GetInstanceFor() method of TQTXWidgetRegistry. Whenever a widget is created it registers itself there, exactly so its easy to do a quick lookup of a handle:

procedure HandleClick(Sender: TQTXDOMPointerDelegate; EventObj: JPointerEvent);

begin

var lHit := TQTXWidgetRegistry.GetInstanceFor( EventObj.target );

if lHit <> nil then

begin

writelnF("you hit %s", [lHit.Classname]);

end;

end;

But what if you have child elements that you populate with raw html or images at runtime? Like I mentioned above the runtime keeps track of widgets you create (or that the application itself has created), but this does not cover raw html that you insert at runtime.

If i have a button as a child on my custom widget (just an example) and insert the following at runtime, those elements will be unmanaged by your application. They are not created as widgets, and thus there will be no registration for them:

button1.innerHTML := '<img src='glyph.png'>&nbsp;Hello world';

So if a user now clicks the IMG element head-on, the target property will in fact point to the IMG element, not your button. And thus getInstanceFor() will return NIL. In this particular scenario the currentTarget propery will in fact point to the button, but we want to avoid such specific situation dependent code if we can.

Finding the owner

TQTXWidgetRegistry has another method that takes care of this, namely a function that will take any handle -then traverse backwards through it’s parents until it find a widget of a specific type – namely FindWidgetFromHandle().

So to mitigate cases where you (or anyone who use your cool new widget) have inserted raw html, you would do something like this:

procedure HandleClick(Sender: TQTXDOMPointerDelegate; EventObj: JPointerEvent);

begin

var lHit := TQTXWidgetRegistry.GetInstanceFor( EventObj.target );

if lHit = nil then

TQTXWidgetRegistry.FindWidgetFromHandle(TQTXButton, EventObj.target, lHit);

if lHit <> nil then

begin

writelnF("you hit %s", [lHit.Classname]);

end;

end;

In the above code we call on FindWidgetFromHandle() and we specify that it should stop if it finds an instance of TQTXButton and keep that value (the third parameter is of type var, so the value is stored there when successful).

This obviously takes for granted that you know the types of child elements you manage. The benefit of custom widgets is that you already know what type of child elements you deal with. A listbox deals with listitems, a listview operates with listviewitems and so on.

You can implement more elaborate code that determine if an element is a direct child of your widget (and thus allowed) and then write more delicate handling to deal with edge cases. If you snoop around the RTL and look at how we have solved things there you will find quite a lot of it!

Adopting a handle

There is also a final option when it comes to “alien” handles, and that is to adopt them! Yes you read that right, you can in fact absorb any element if you have a handle reference.

TQTXWidget which is the fundamental class for all visible controls have a few constructors you can pick from, including one that takes an already existing handle.

So you can in fact do something like this:

var lAlien := TQTXWidget.CreateByRef(EventObj.Target, [], nil);

In some circumstances it’s actually very useful to inject raw HTML, and then adopt the injected structure as a widget. It all depends on your needs.

The second parameter is a set type, with a few options you can tweak:

TQTXWidgetCreateOptions = set of (

wmStyleObject,

wmBindToParent,

wmUsePositionMode,

wmUseDisplayMode,

wmUseOverflow,

wmUseBoxSizing,

wmUseParentFont,

wmUseTouchAction,

wmUseVisibility,

wmAutoZindex

);

These options enable or disable what should be applied to the handle. wmStyleObject will execute the StyleObject() method as a part of the constructor, Using wmUseParentFont will apply the parentfont styling to the widget and so on. In most cases you wont apply any of these as that would affect how the adopted element is styled.

Do keep in mind though that adopted widgets will not manage the element’s life-cycle like ordinary widgets. Since the element was not created by TQTXWidget, it will not destroy the HTML element it manages when the destructor executes.